Digging Deeper Into Who You Are

Digging into your family’s history is a very personal journey.

Digging into your family’s history is a very personal journey.

My interview in the January issue of Main Street Magazine explores how inspiring that journey can be.

Read Full Article Here:

Digging Deeper Into Who You Are;

Main Street Magazine, January 2021

When people think about their family tree and wanting to know more, what is it that they are longing for? It’s the stories. How did family members manage in difficult circumstances? What were their challenges? The details of their lives show how and why they made their choices.

We hold the legacies of [our own] stories in our hands. This past year may be one we all want to scratch, but our children and grandchildren will want to know what it was like. They will have no idea, unless we bring the stories to them.

Keren Weiner; Digging Into Our Roots, Main Street Magazine

Tracing Our Roots

My work was featured in the January 2018 issue of Berkshire Jewish Voice.

My work was featured in the January 2018 issue of Berkshire Jewish Voice.

In the article, I describe the impact of genealogy, a bit about my methods, and in particular, my approach to Jewish genealogy.

Read Full Article Here:

Tracing Our Roots

Berkshire Jewish Voice, January 2018

“Getting connected to a timeline can be revelatory. It can change the way a person looks at life and family. . . . Preserving the stories of the past and capturing documents that fill in our back stories lets us draw threads of experience through our own lives and preserve them for future generations.”

It’s Not So Hard to Get a Patent

Solomon and Hannah Menkin moved to America in 1888. Tracking them after that gets a little tricky.

Solomon and Hannah Menkin moved to America in 1888. Tracking them after that gets a little tricky.

In the first place, the 1890 U.S. Census, had it survived, would have been central to finding more information. Tragically, the 1890 Census was almost completely destroyed in a terrible archive fire in 1921. The loss of this priceless census creates massive brick walls that sometimes take a lot of effort to break through. The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) website tells the intriguing story of this fire and the loss of this part of our history.

The next census we can get our hands on for Solomon Menkin is the 1900 U.S. Census – showing that his occupation is “toolmaker.” According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there were 28,122 people who identified themselves as toolmakers in the 1900 U.S. Federal Census. The 1910 U.S. Federal Census also shows “toolmaker” for his occupation, and it is not until the 1920 U.S. Census Federal Census, that his occupation is listed as “Mechanic – Button Factory,” with the additional indication that he is an employer.

I used to play with buttons as a kid. This was before the rise of the great game and toy manufacturing industry and the marketing that accompanied it. In the 1950s, we played with golf balls and jacks, acorns, items from Dad’s tackle box that did not have hooks, and BUTTONS, which I kept in a cigar box!

So to learn more about the occupation, and the first immigrant ancestor in my current research study, I simply Googled, “Solomon Menkin button.” Lo’ and behold, the first item in the search results was in “Google Patents,” Patent No. US586821 – Button-making machine. Clicking on that result yielded his date and place of filing, the text of the patent and accompanying diagrams, and, to my surprise, a link to a 2001 patent filing for a solid-state image-sensing device which cited Menkin’s original patent. There was also a link to original images located in the online database of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO.gov). You can also search for patents with USPTO.gov’s patent search feature, using inventor name, patent number, and other search terms. I tried this, and found a second patent for Solomon Menkin. Thanks go to Google and USPTO.gov for allowing another aspect of family history research to unfold.

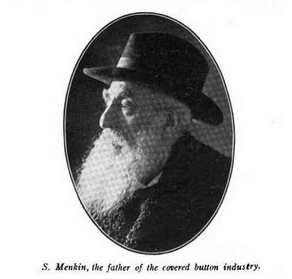

So you see, it is not so hard to get a patent – a copy of one, that is. In the process we learn so much about our ancestors and their life’s work. This was only the beginning in our search to learn more about the life and legacy of Solomon Menkin. The icing on the cake was a slightly different Google search with the term, “S. Menkin button” which offered an article AND a photograph of the inventor himself in a 1916 issue of the trade journal, Notions and Fancy Goods, in which he was lauded as “the father of the covered button industry.” In family history research sometimes, it doesn’t get better than that.

What if you came to Ellis Island and were turned away?

In 1905, a young man and his pregnant wife sailed from Glasgow to New York, after escaping from Russia during a period of intense pogrom activity. When the ship landed in New York, the young man was most anxious to get his wife safely settled for the child’s birth and to join his three older brothers who had already arrived and started their new life in America.

The ship record was my first clue that something had gone wrong when the couple reached Ellis Island. In the far right hand margin of the passenger list, there was a handwritten note regarding the young man’s medical condition, “barber’s itch” and in the far left-hand margin, the letters “SI” (Special Inquiry) appeared and the word “deported” had been ink-stamped. Their names also appeared on a separate “Record of Detained Passenger” with the notations, “Hold on Appeal” and “Appeal dismissed, ordered deported.”

Barber’s itch was the name of a highly contagious condition, and when diagnosed by one of the medical examiners at Ellis Island, was one of the diseases that resulted in the barring of immigrants from approval to enter the U.S.

What happened between their landing at Ellis Island, full of hope, and their deportation? First, they would have been held for a special inquiry in a room with other immigrants awaiting determination. Approximately 20% of immigrants to the U.S. would be held for some length of time. Stories about this interim detention vary widely. Some immigrants have reported that they were held in clean, sanitary rooms and were humanely treated. Others report that they were detained in cramped areas with poor ventilation. Regardless of their experience while waiting for approval to enter, 2% would be refused admission. Immigrants who were held aside were brought before a Board of Special Inquiry, which heard each case privately. An interpreter was usually present and witnesses were allowed. (Island of Hope, Island of Tears, by David Brownstone, Irene Franck and Douglass Brownstone; Barnes and Noble, New York, NY: 2000; 213).

During this particular hearing, the couple gave testimony and one of his brothers arrived to testify for him. Since the couple did not arrive with extra funds, the Board of Special Inquiry pronounced the couple a “likely public charge” meaning that they did not have the means to support themselves, which also contributed to the final determination to deport them.

I had imagined this hearing to take place in a large courtroom. The actual hearing room, I discovered, was much smaller than I visualized. As I stood at the door and peered into the hearing room (access into the room was not available), I thought about how afraid this young man would be, how worried he would be for both of them. I thought about the young woman, worried for her husband and the child she carried. It was a sad scene I could feel, even from the distance of one hundred and ten years.

After the decision was made to deport them, an appeal was filed to the Commissioner-General of Immigration in Washington, D.C.

During the appeal, testimony was supplied indicating that the young man had a temporary condition resulting from being shaved under unsanitary conditions, or if it was Barber’s Itch, it was a very mild case that could improve in two to three weeks. The relatives, it was promised, were willing to pay for the medical treatment while the couple was detained. The young man was described as being skillful at his trade and fully capable to support himself and his wife (refuting the label “likely public charge”).

Their case was carefully reviewed and the couple questioned again while remaining in the detention quarters. In spite of the prospects for a successful immigration, due to the medical condition and the commission’s belief that they would not be able to make it financially, it was recommended that the Board of Inquiry decision be affirmed and that the appellants be deported.

As a genealogist and family historian, I wanted to know if it was possible to get a copy of the appeal transcript. With guidance from Marian L. Smith, Senior Historian at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS), I sent an inquiry to the National Archives in Washington, D.C. for a search in Record Group 85, which contains immigration correspondence files. The USCIS website at www.uscis.gov provides a description of the records in Record Group 85.

The National Archives returned a fascinating document of the hearing and appeal that included responses to questions by the immigrant couple, testimony of the brother who appeared, and the text of the decision by the Commissioner to deport. Valuable genealogical information was included in the content of the file revealing clues for further search on the older brother who testified and necessary information to follow the couple after their deportation.

Our National Archives hold treasure after treasure, in this case, a document that allowed us to time-travel.

Wondering what happened to the young couple? Even better, contact me if I can help you to look into your own family history for poignant stories, historical documents and a new understanding about the present from the past.

Ellis Island in 1905; photo by A. Coeffler (Library of Congress)

What does the search for the Ivory-billed woodpecker have to do with the Civil War?

In 1859, a young man graduated from the University of Louisiana with a degree of Doctor of Medicine. He moved his North Carolina family to Madison Parish, Louisiana, and then came the Civil War. The family owned a plantation there, and the family name appears on an 1862-1863 map showing the names of plantation owners, abandoned plantations, roads, villages, rivers, etc.

In 1859, a young man graduated from the University of Louisiana with a degree of Doctor of Medicine. He moved his North Carolina family to Madison Parish, Louisiana, and then came the Civil War. The family owned a plantation there, and the family name appears on an 1862-1863 map showing the names of plantation owners, abandoned plantations, roads, villages, rivers, etc.

I found the map on a website for the digital historical maps of Louisiana, coordinated by Richard P. Sevier. He notes that this Confederate military map was captured by Union forces and was probably a forerunner to the Grant’s March map. See http://www.usgwarchives.net/maps/louisiana/.

While it was wonderful to find a Civil War era map showing this family’s surname, I was puzzled and intrigued when I saw the additional note, “Courtesy of the USGS National Wetlands Research Center.”

Wetlands research? There had to be a story there, so I decided to email the National Wetlands Research Center to find out what it was.

NWRC responded that the map was discovered by a group of scientists at the National Wetlands Research Center while they were conducting research on the now extinct Ivory-billed woodpecker in the Tallulah, LA region. Their scientists acquired the map from the Watson Library at Northwestern State University of Louisiana, Natchitoches, Louisiana, who acquired the map from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Scans were shared with Mr. Richard Sevier at USGenWeb and they were assembled into the map we see online. “According to the memory of those involved, this map was supposedly one of several Confederate maps captured by the Yankees during the Civil War.”

Fascinating.

So, a grateful thank you to the map’s original creator(s), thank you to whoever gave it to our wonderful National Archives, to the Watson Library archivists, to Mr. Sevier, to NWRC and thank you to all the people who value and take care of our precious national history.